In 1975, during an interview conducted by l’INA Société France, individuals were asked the following question: "What is it to be a woman?" (“C’est quoi une femme?”, 1975, Paris). Now, nearly 50 years later, this question still echoes, resonating with new meanings and challenges

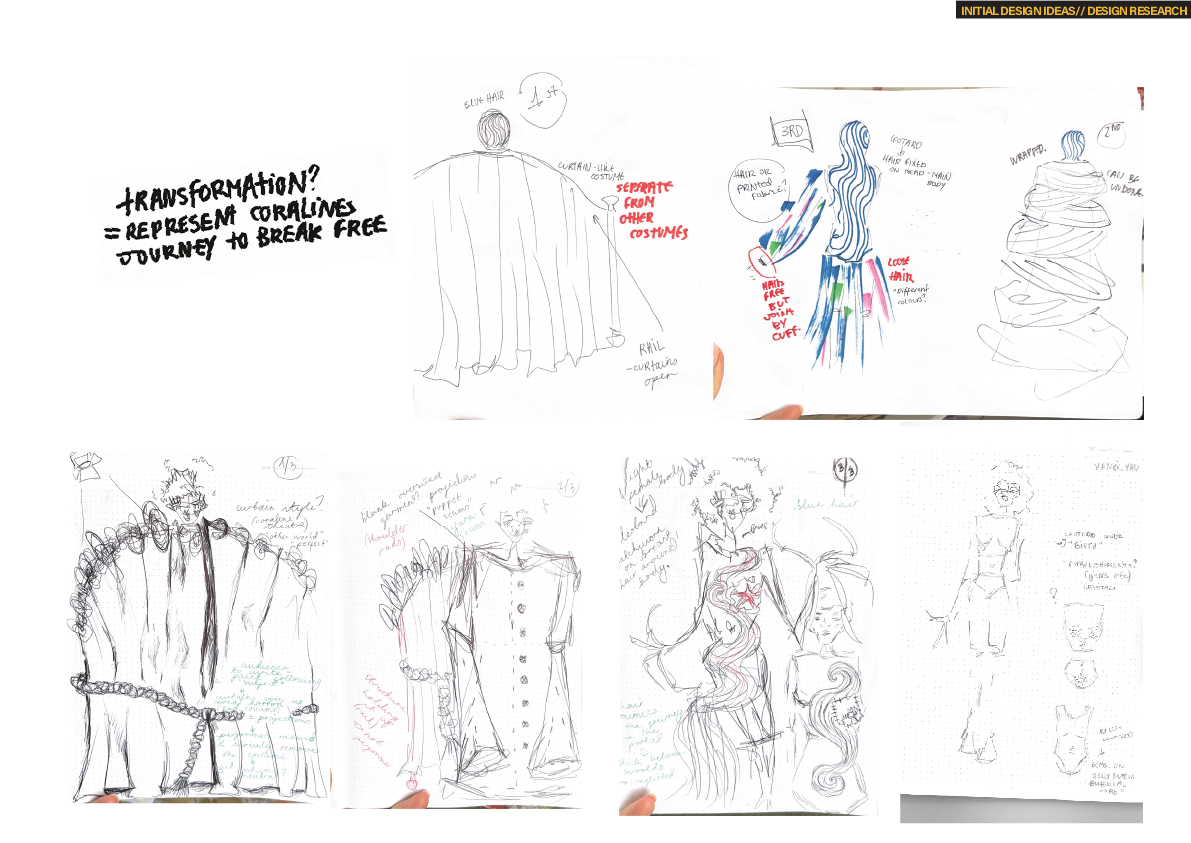

L’Autre (“The Other”, ref: The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir) explores how women’s perspectives on womanhood have evolved since 1975 and the societal pressures that continue to shape female identity. Using costume design, and Neil Gaiman’s Coraline as a visual and thematic framework, the project investigates the psychological, social, and historical influences on women’s lives.

My goal aims to encourage the audience to reflect on how gender expectations still shape women's lives and to consider how these expectations can be broken down. Just like Coraline moves between her world and the Other World, women today are constantly navigating the challenges of modern womanhood, finding strength and empowerment while still facing the limits society places on them.

This body of work is dedicated to all women around the world, with a special thought for my family, and in particular my younger sister, whose strength and determination continue to inspire me every day.

*Final work presented as a performance film, combining projections, sound, dance & costume. All materials for 3 costumes were entirely up-cycled.

April 2025.

Directed & Produced by Chiara Hodgson

Costume Design by Chiara Hodgson

Performed by Yanki Yau

Digital montage by Chiara Hodgson

Cinematography by Nick Sargeant & Dan Adakpor

Choreography by Tia Hockey

Course Director: Agnes Treplin

Technical support: Guilia Pecorari, Vic Aubrey, Ben Turnbell, Helena Hodgson

Portfolio

Behind the scenes

The following dissertation was written solely by Chiara Hodgson, excluding cited material. It may not be copied, reproduced, or used for personal, commercial, or educational purposes.

“L’autre”: How have women's perspectives on the concept of womanhood evolved since 1975, and what are the contemporary challenges and opportunities facing women under constant societal pressure? - Explored through Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and the medium of costume design.

Introduction

In 1975, during an interview conducted by l’INA Société France, individuals were asked the following question: "What is it to be a woman?" (“C’est quoi une femme?”, 1975, Paris). Now, nearly 50 years later, this question still echoes, resonating with new meanings and challenges. My research aims to revisit this question, using social investigation to explore how women’s perspectives on womanhood have evolved over time, and what it means to be a woman in today's society.

This project is an exploration of the ways in which women’s identities have been shaped by historical and cultural forces since 1975, and how societal pressures continue to impact women’s understanding of themselves. By using costume design and performance, I hope to provoke reflection and self-awareness in the audience, challenging their notions of womanhood and identity. The choice of Coraline as a storyline for my work plays a key element in this project. It is a dark fantasy about a young girl who discovers a parallel world that initially seems better than her own, only to uncover its wicked nature. Its exploration of alternative realities, societal control, and the struggle for autonomy, reflects how women have always dealt with the expectations and limitations placed on them.

The evolution of womanhood since 1975, has been shaped by significant political and social shifts, such as the rise of feminism, the challenge to traditional gender roles, and the fight for reproductive rights. Despite significant advancements in gender equality, many of the pressures women face today remain largely unchanged, or have evolved into more subtle forms. Women are still subjected to the idealisation of their physical appearance, which is created by societal standards and also the media. Additionally, the underrepresentation of women in key media roles continues to influence public perceptions and limit opportunities. Another challenge is the expectation that women should constantly juggle multiple roles: caregiver, professional, partner, often leading to a "second shift" of unpaid domestic labor. Single mothers face the burden of balancing work, childcare, and often limited financial resources, making it difficult to escape cycles of poverty.

Also women’s safety remains an ongoing concern, with street harassment and the threat of violence in daily life. The influence of the male gaze and toxic masculinity objectifies women, limiting their freedom in public and private spaces. I personally feel this on a daily basis. I grew up hearing my mother warn me to avoid staying out too late, always concerned for my safety. This constant reminder of vulnerability is a reality most women experience.

Furthermore, women’s healthcare remains a contentious issue. The reduction of abortion rights in the United States, following the Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, highlights the persistent struggle over control of female bodies. Frida Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital (1932) is a representation of female pain and reproductive trauma, depicting her own miscarriage in a brutal manner. More recently, Danica Lundy’s Boombox explores female suffering without placing blame on its subject, highlighting how pain is often normalised or dismissed.

Worsening the issue, female genital mutilation (FGM) remains a human rights violation affecting millions of women worldwide. The 200 MILLION Girls Cut Worldwide documentary sheds light on the survivors of FGM and the cultural pressures that keep these practices alive, showing the patriarchal control over women’s bodies. My mother, Agnès, a human rights lawyer specialising in international law, has worked with countless women fleeing their home countries to seek asylum in France, escaping not only FGM but also forced child marriage and other forms of gender-based violence. As she mentioned in her interview, "These women are running for their lives, not just from war, but from their own communities, from the very people meant to protect them." Her words showcase the urgency of this issue, reminding me that while discussions of gender equality often focus on Western contexts, for many women, simply existing outside of oppressive cultural expectations is a matter of survival.

In addition, women still face significant struggles for equality in their professional and personal lives, facing barriers like unequal pay, limited career advancement, and unfair distribution of family responsibilities. According to the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2021, it will take an estimated 135.6 years to close the gender gap in economic participation and opportunity. These issues highlight the complexity of gender inequality, deeply impacting women's experiences, especially for those in marginalised communities. Michelle Obama emphasises the importance of education in driving change, stating, “When we invest in girls, we are investing in the next generation of mothers, daughters, workers, and leaders” (2018). This highlights how empowering women through education is vital for breaking the cycle of poverty and inequality.

My choice to explore Coraline through costume and film was driven by its metaphorical strength in showcasing the contrasting worlds women navigate. The “Other World,” which seems to offer the illusion of comfort and perfection, becomes a symbol of the pressures women face to conform, while Coraline’s escape acts as metaphors for breaking free from societal control and gaining control. My costume designs act as a visual and emotional language, communicating these struggles through fabric, shape, and movement. By incorporating elements of personal research, including interviews with women from various backgrounds, the costumes are not just symbolic of a concept but are grounded in lived experiences.

The inspiration for this project also draws heavily on my previous work on female street harassment, where I began to understand the psychological impact of societal pressures on women’s identities. This project is a continuation of that inquiry, but on a broader scale, tackling womanhood from its social, psychological, and historical perspectives. Additionally, my interest in sustainability and up-cycling influenced the materials I used.

This project is more than just a performance, it’s a way to highlight the ongoing struggles women face while also offering a deeper, emotional reflection on their journey. Its focus is to promote a conversation about women’s rights, identity, and the shared responsibility of society in breaking the chains of expectation. I hope to encourage the audience to reflect on their own roles in maintaining or changing societal expectations around gender.

Chapter 1: Analysis and Interpretation

By combining sociological research with costume design, I have developed an immersive experience that audibly and visually narrates the journey of women through an ever-changing societal framework. The primary thematic concern of my project lies in the question of what it means to be a woman and how this identity is constructed and deconstructed in the face of evolving pressures.

Through the interviews I conducted, I wanted to compare the perspectives of women today with the interviews from 1975, L’INA. The responses reveal that opinions and struggles around womanhood have not shifted much over the decades. Many women spoke about the challenges of being a single mother (Maja), “feeling uncomfortable due to the male gaze” (Logan), and “struggling to balance work and family” (Kathy). One participant shared how her culture deprives women of their rights, and how she constantly feels the pressure to act in a way that meets family expectations (Gul). These experiences resonate deeply in my project, reflecting how societal expectations often suppress women's true selves. The idea of the "Other," as discussed by Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex, is key to understanding the subtle societal pressures that define what is considered "acceptable" womanhood versus what is seen as "other" or "subversive." De Beauvoir stated "one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman" (1949), which highlights the idea that womanhood is a social construct rather than an identity. This idea is particularly relevant when considering the projections of idealised femininity that women are often expected to perform. As she further explained, "The myth of woman as the 'other' defines her only in terms of what she is not.”.

The concept of the "Other" directly connects to female marginalisation, where women have often been defined in relation to men and shaped by patriarchal expectations. This theme is evident in Coraline’s "Other Mother," who seems to present an idealised version of domesticity and femininity but actually represents an oppressive force that traps Coraline in a twisted reality. My costume designs reflects the changing phases of this societal prison.

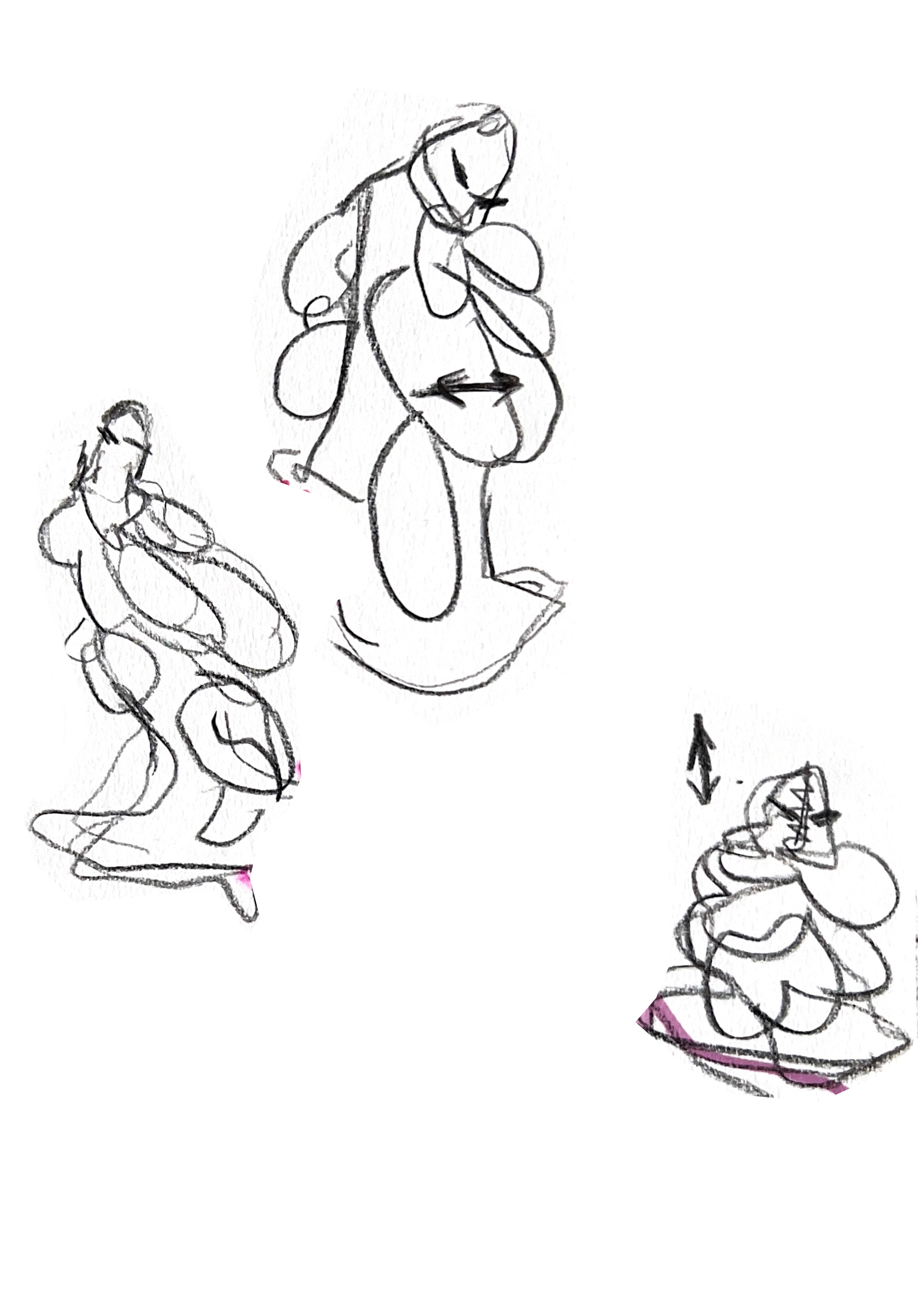

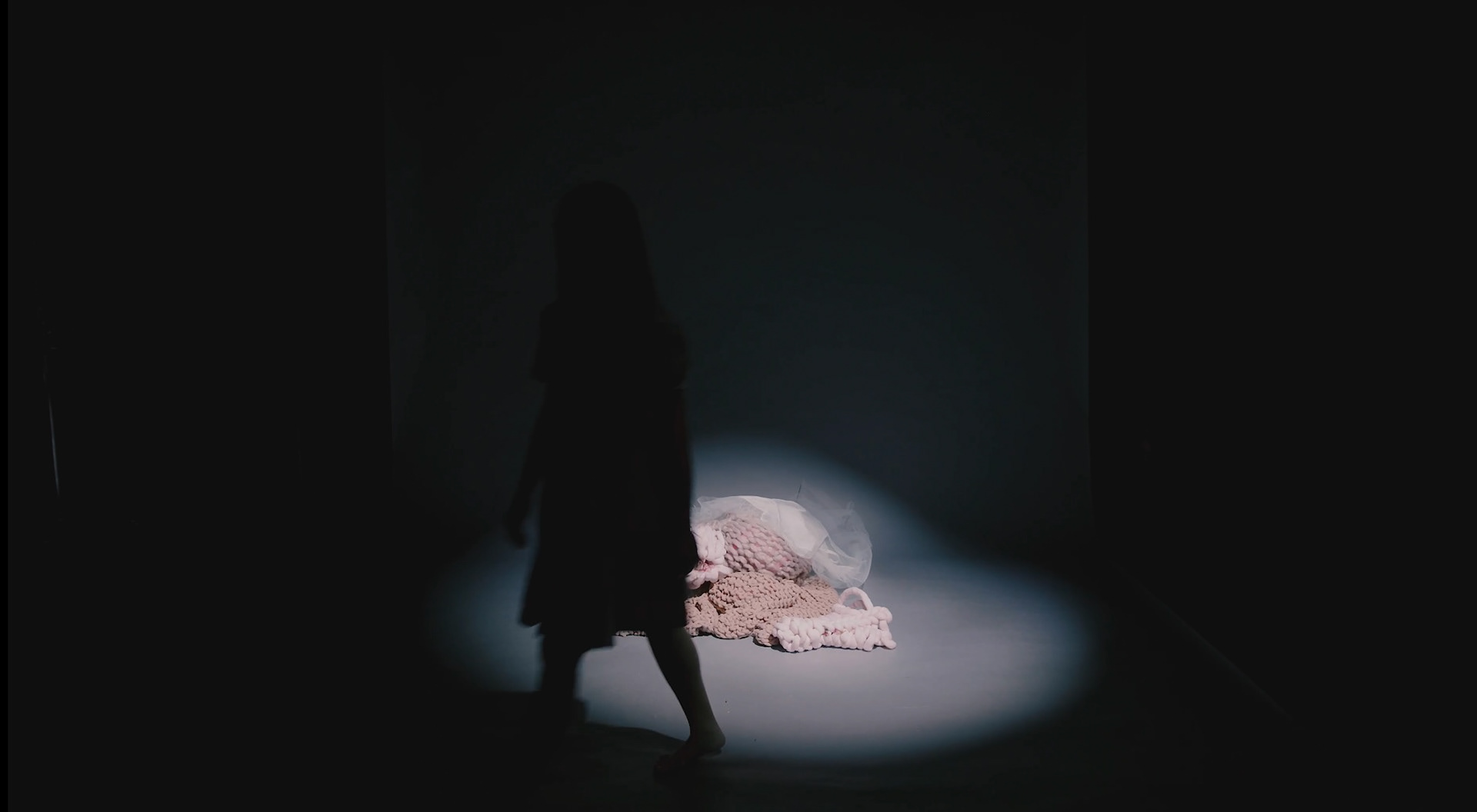

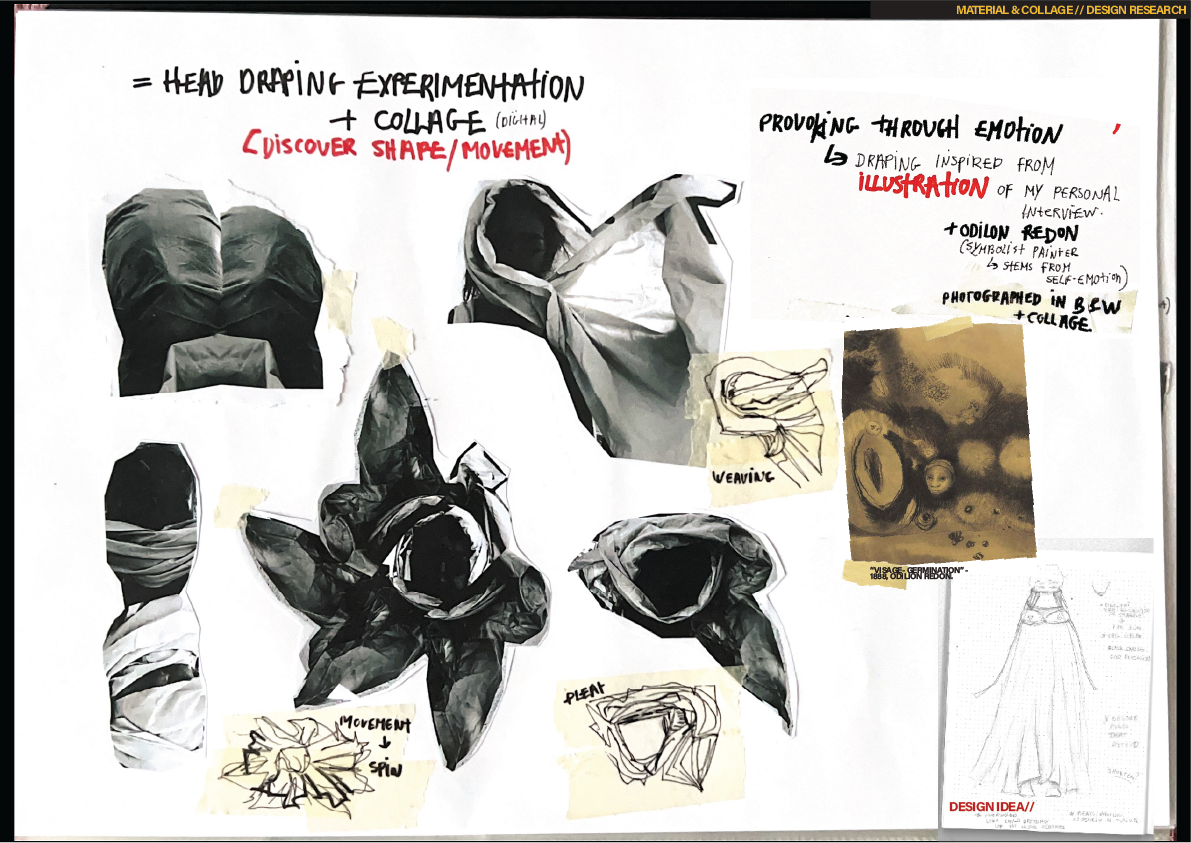

The first costume in my project, representing the Other Mother, uses materials such as soft yarn and crochet to create a tactile, almost comforting feeling, like a cocoon. However, this comfort hides the harsh truth: the yarn and crochet form a metaphorical "cage," symbolises the confinement women face in society’s defined roles. These materials also evoke stereotypical notions of femininity, such as softness, innocence, and nurturing, but ultimately, these qualities are used against women to perpetuate societal control. I also incorporated a crocheted and beaded section representing something sacred to women, their genitalia. Inspired by my research on FGM, this element resembles a bleeding vulva in a symbolic, non-gruesome way, turning pain into something precious. The costume’s breast-like forms act as a distortion of the body, exaggerating and reclaiming symbols often used to define and confine women. These forms represent both the nurturing aspect of femininity and the societal pressure placed on women to conform to certain ideals. I intended to reclaim breasts, as symbols of motherhood and life, in a way that empowers women rather than confines them. In the choreography, the performer’s gradual realisation of this oppressive reality, through soft, and fluid movements, reflect the moment when a woman begins to question her place within this constructed "perfect" world.

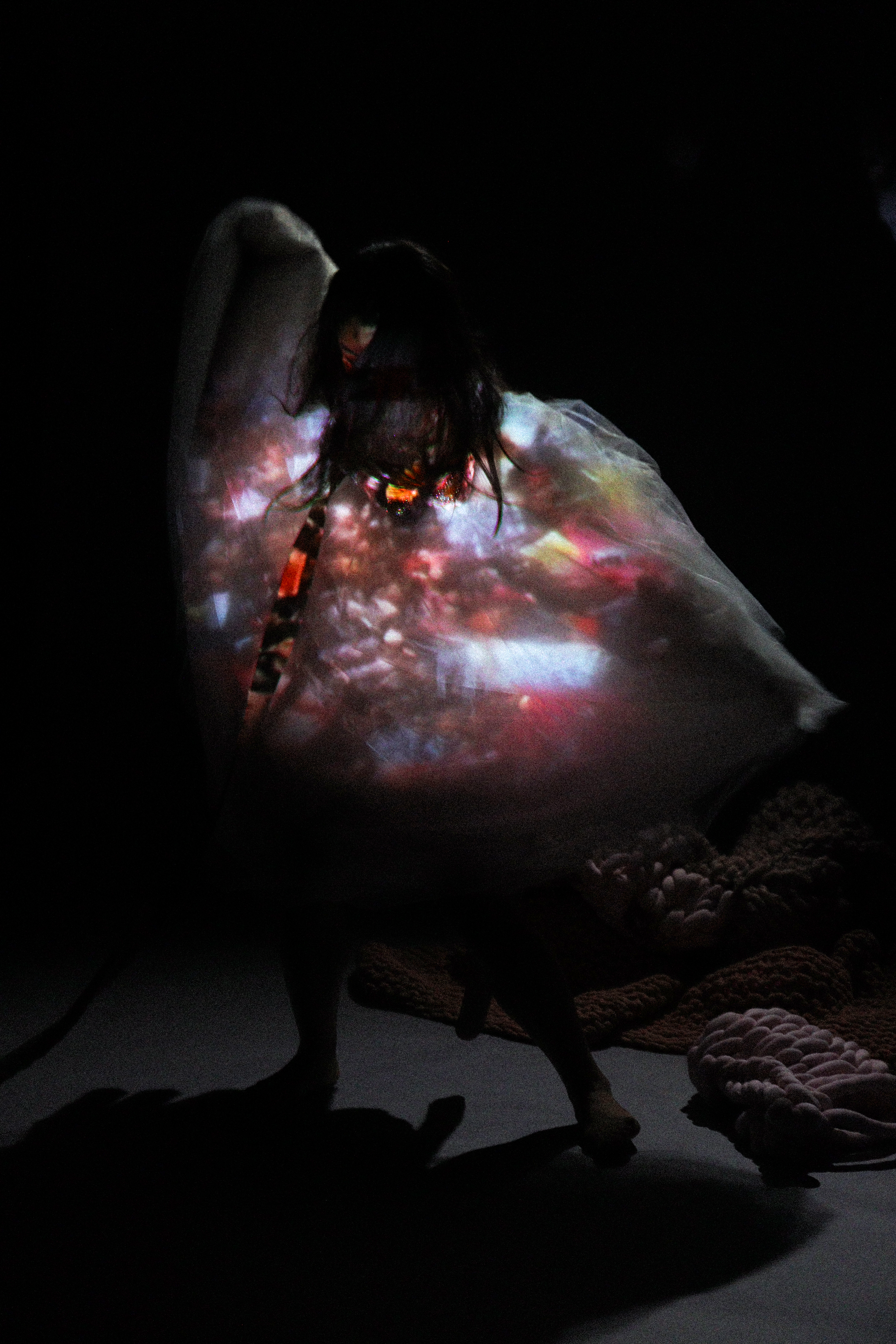

The second costume introduces a transformation where the societal "cage" is revealed for what it truly is, and the performer is exposed to the viewer, not as a passive subject, but as an active participant in the process of self-discovery. I chose to use a projection based design that acts as both a visual barrier and an educational tool, reflecting the complex layers of societal expectations that have shaped women’s identities since 1975. The montage with audio, projected onto the costume includes my social research, interviews, and various media sources, creating an experiential learning moment for the audience. These projections allow the performer to embody the knowledge, struggles, and voices of women from various backgrounds, giving the costume a dynamic, living quality. The layers of fabric reflect the many facets of the societal issues women encounter, highlighting the diverse yet connected struggles they face today.

The second costume also includes puppet-like features, representing how society often treats women as puppets, controlled by its expectations. This design highlights the power dynamics involved, with the strings evoking the Other Mother's control over Coraline, reminding us of the outside forces that try to direct women's paths. The collar, crochet fabric, and neck ties emphasise this notion of societal control, which may appear comforting at first but is actually suffocating.

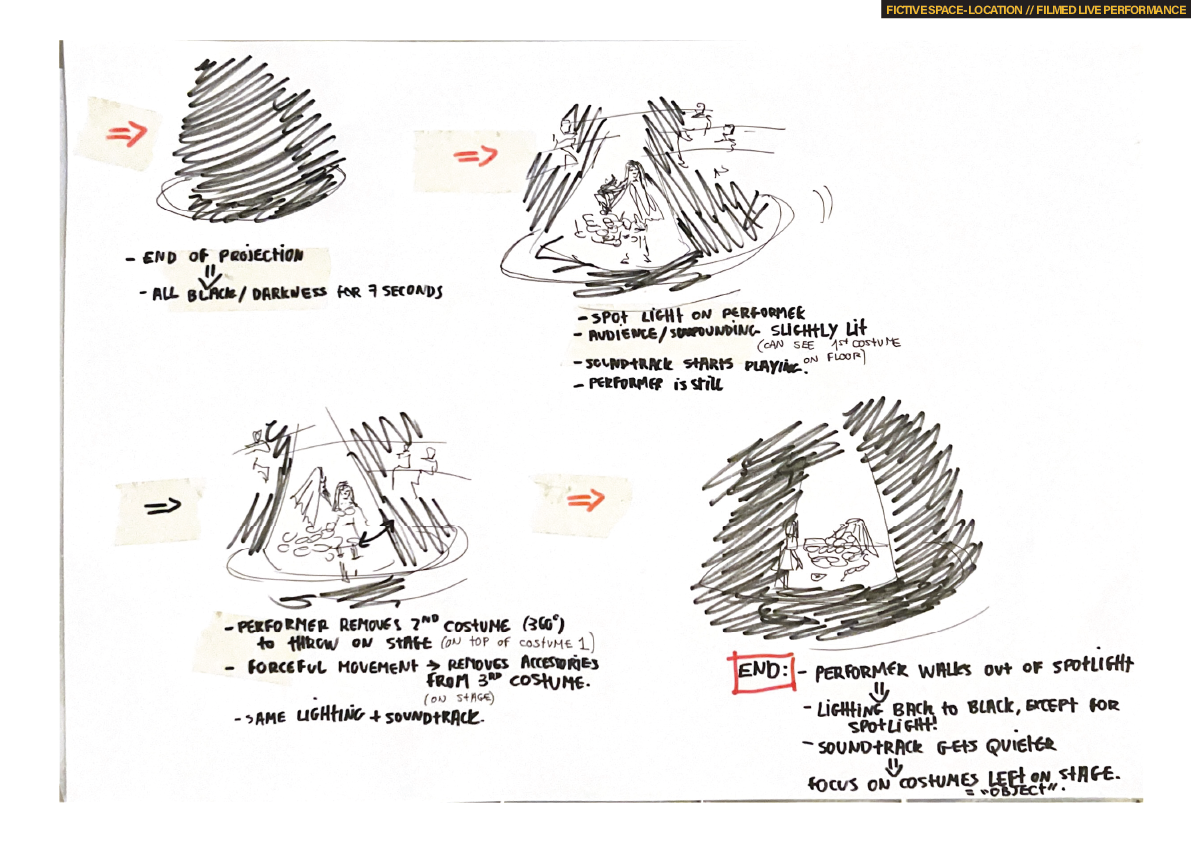

The final costume, revealed as the performer sheds the previous layer, signifies a symbolic rebirth. The nude, skin-like dress, decorated with drawings that depict women's journeys, embodies the freedom of self-expression and the confrontation with identity and body. The drawings are inspired by protest banners, symbolising elements from my research, in particular my drawing interpretations from the interviews . This final garment represents women’s empowerment as they take ownership of their bodies, identities, and futures. The beaded accessories, which represents societal constraints, are removed, highlighting the performer’s rejection of conformity and her commitment to creating a new path.

The transformation of the costumes visually represents the journey from restriction to liberation, ignorance to knowledge, and victimhood to agency. By blending different textures, materials, and projections, I aimed to illustrate how these elements serve as metaphors for the pressures women encounter and how they can be transcended. The shift in the costumes from confinement to freedom reflects the process of self-discovery women undergo as they navigate societal constraints.

Besides the narrative structure of the costumes, movement is vital in expressing the emotional and psychological journey. The performer’s choreography captures the internal battle of escaping societal control, featuring a range of movements from hesitant and restrained to bold and powerful. The costume needs to complement this movement, amplifying the performance's emotional impact. For instance, when the dancer sheds the second, restrictive costume, it creates a cathartic moment that symbolises both physical and emotional freedom.

This part of the essay highlights the significance of costume design not just as a visual element but also as a way to convey psychological and emotional stories. By using a layered approach that includes materials, projections, and movement, I aimed to enhance the audience's understanding of womanhood and its evolution. The design choices are meant to encourage reflection, challenge stereotypes, and raise awareness of how society continues to impact and shape women's identities.

Chapter 2: Contextualisation

A strong inspiration for this project was drawn from the women surrounding me whose experiences, struggles, and triumphs shape the reality of modern womanhood. This is why it was so important to incorporate both a social and psychological aspect into my work, ensuring that it was not only artistically compelling but also deeply rooted in real experiences. To achieve this, I conducted social research, including interviews (visual and audio for choice of anonymity) and surveys, to understand how gender expectations continue to affect women’s lives today. This direct engagement with women’s voices has shaped my approach, making it a crucial foundation for my creative process.

To better understand my design choices, it’s important to place this project within a wider cultural, artistic, and psychological context. This chapter explores how my work connects with feminist art movements, contemporary activism, and psychological theories, situating it among artists, thinkers, and researchers who have tackled similar themes.

Feminist art has long focused on how women's experiences are represented visually, often challenging traditional notions of beauty, femininity, and gender roles. The work of artists like Judy Chicago and Yoko Ono, whose pieces tackle gender inequality, identity, and power, has been instrumental in shaping my approach. Chicago's The Dinner Party and Ono's Cut Piece specifically confront the expectations placed on women and demonstrate how reclaiming agency through art can provoke social change. As Chicago asserts, "Art can be a vehicle for creating new symbols, a new iconography that expresses the experiences of women rather than suppressing them." (Chicago, 1979). These works, which involve performance and audience interaction, underscore how art can act as both a mirror of societal issues and a catalyst for change.

Similarly, artists such as Louise Bourgeois, known for her exploration of the female body in relation to power and vulnerability, have influenced my approach. Bourgeois' art often incorporates personal experiences to address universal themes like identity, trauma, and liberation, ideas that resonate deeply with my own exploration of womanhood. In reflecting on her own work, Bourgeois stated, "Art is a guarantee of sanity. That is the most important thing I have said."(Bourgeois, 1993). This statement aligns with my approach to costume design, where the visual representation of emotional and physical transformation invites the audience to engage with both the psychological and intellectual facets of womanhood.

The physicality of performance and movement is also central to the work, and draws inspiration from artists like Pina Bausch and Marina Abramović. Both used the human body to express raw emotion and challenge societal norms, focusing on how performative acts shape identity. Abramović’s endurance-based performances emphasise the ways in which societal pressures push individuals, particularly women, to their limits. As she reflects, "The hardest thing is to do something which is close to nothing, because it is demanding all of you." (Abramović, 2010). This idea of endurance, both physical and emotional, deeply connects to the themes of perseverance and societal constraint that I explore in my project.

From a psychological perspective, Freud's theories and the work of contemporary scholars like Gina Rippon, author of The Gendered Brain, provide key insights into my exploration of womanhood. Freud’s ideas on gender identity and the unconscious help explain how women’s societal roles are shaped by both conscious and unconscious forces. Rippon challenges the myth of a "gendered brain," highlighting how such beliefs confine women to biological determinism. As she states, "The message that our brains are uniquely male or female is a powerful one that feeds stereotypes, but neuroscience tells us a different story" (Rippon, 2019).

Alongside the feminist artists and performance theorists who shape my approach, I draw inspiration from contemporary activists like Malala Yousafzai and Michelle Obama, who champion women's rights, education, and empowerment. Their work highlights the ongoing struggle for gender equality and informs my exploration of womanhood. As Michelle Obama states in Becoming, "When girls are educated, their countries become stronger and more prosperous" (Obama, 2018). Similarly, Malala Yousafzai asserts, "We cannot all succeed when half of us are held back" (Yousafzai, 2013). Their activism resonates with my own efforts, as I explore these themes through a different medium to theirs.

Furthermore, sustainability plays a significant role in my design process, reflecting a cultural shift toward eco-consciousness. Using up-cycled materials addresses environmental issues while echoing the themes of transformation and renewal in my project. By recycling materials, I link personal growth and change to sustainability, highlighting that both women and the environment can reimagine and reshape their roles.

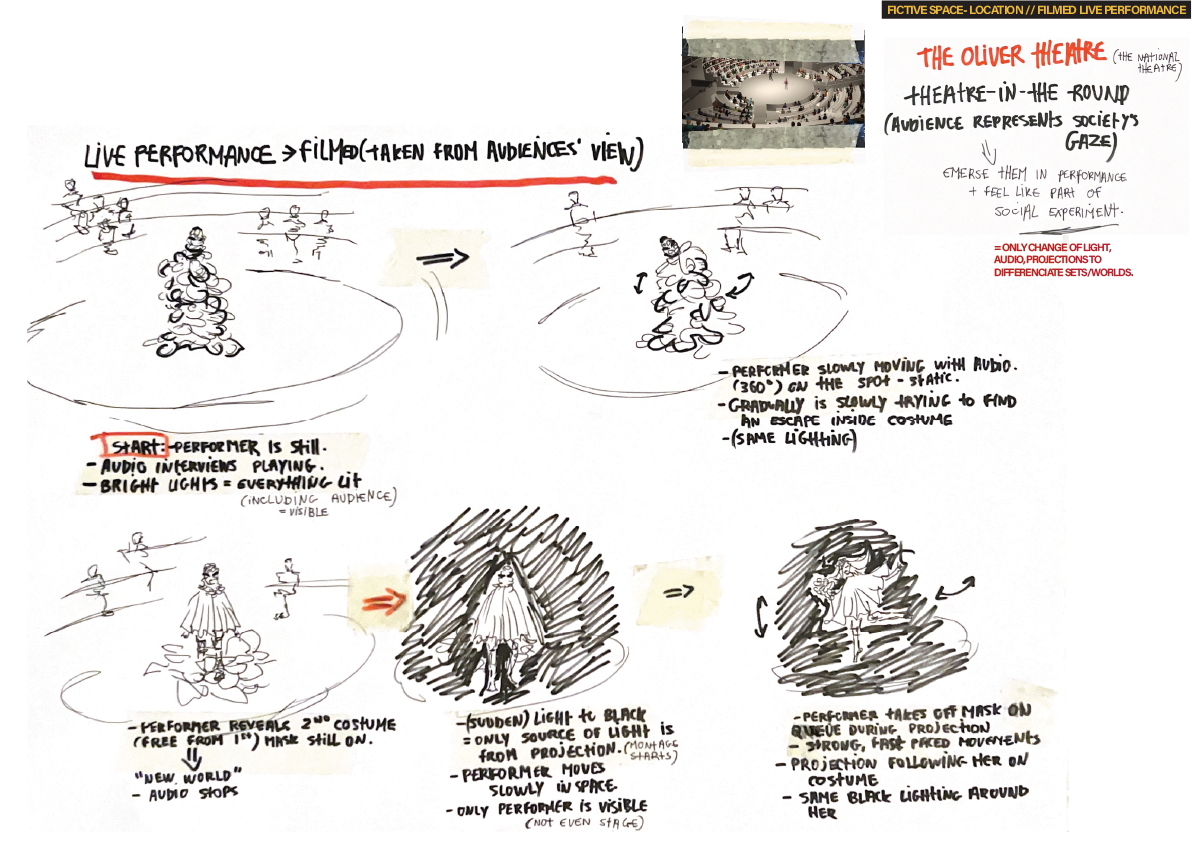

Finally, in terms of setting, I envision it being performed in a theatre-in-the-round, such as the Olivier Theatre in London, where the audience is surrounded by the action. This immersive environment highlights the theme of the societal gaze, making the audience complicit in the performance. The proximity of the audience to the performer intensifies the emotional connection and making the exploration of womanhood more personal.

Chapter 3: Materiality and Symbolism in Costume Design

In this chapter, I further investigate how material choices and symbolism within the costumes play a crucial role in expressing the themes of societal pressures and female empowerment. The notion of womanhood as both a physical and psychological construct becomes central in how we understand the material world around us and how materials shape, distort, and ultimately liberate the identities women are allowed to express. The choices of fabric, texture, and the transformation of materials throughout the performance are used to evoke the constraints of femininity as well as the possibility of liberation from these confines.

I used a mixture of materials such as yarn, crochet, silk, metal, and organic fabrics to convey the contrast between societal constraints and the possibilities of self-empowerment. The initial costume, which represents the "Other Mother," uses soft, homely materials like yarn, which are conventionally associated with warmth, care, and femininity. However, when these materials are manipulated into a rigid structure, they also evoke a sense of suffocation and confinement, representing how societal expectations have trapped women in defined roles. The materiality of yarn, often associated with domesticity and traditional notions of femininity, paradoxically becomes a symbol of oppression.

The use of crochet is particularly significant in this context. The repetitive, almost obsessive nature of crochet speaks to the way in which society imposes a strict, cyclical form of femininity on women. It represents the creation of a "perfect" reality where the pressure to conform to these norms can feel suffocating. The performer's movement is initially restricted by the heavy, knot-like nature of the crochet, symbolising the inability to break free from societal expectations. However, as the performer begins to release herself from this costume, the sense of liberation grows stronger, reflecting the potential for breaking free from societal constraints.

In contrast, the second costume introduces more fluid and dynamic materials, such as silk and draped fabrics, while still wearing the crochet mask. These materials symbolise the transition from restriction to liberation, representing the woman who begins to deconstruct the prescribed roles assigned to her. The loose, flowing nature of these fabrics allows for a greater range of movement, both literally and metaphorically. Once the mask is removed during the monologue/projection sequence, it signifies the empowerment of women as they reject the notion of being confined to a passive role and instead embrace autonomy.

The projections on this costume also contribute to its materiality, enhancing its theatricality and drawing inspiration from Coraline’s interplay of light and shadow to create a shifting reality. The images projected onto the fabric serve to layer the material with meaning, turning it from a passive object to an active. Featuring interviews, archival footage, and powerful imagery from women’s movements, the projections symbolise historical struggles for equality, rights, and agency. By allowing the material of the costume to interact with these projections, I am emphasising the idea that identity is constantly evolving and shaped by both internal desires and external societal forces. The shifting visuals reinforce this notion, blurring the line between self-perception and societal expectation.

The third costume further embodies the theme of liberation and self-expression through the choice of nude, skin-like fabrics. These materials are meant to evoke vulnerability and authenticity, as well as the shedding of societal expectations. The transparent nature of the fabric emphasises the idea of stripping away the layers that have previously hidden the true self. The addition of hand-drawn sketches on the garment acts as a direct, personal interaction with the costume, reflecting the performer's journey of self-discovery and transformation.

The beaded accessories incorporated into the final costume symbolise the societal constraints women face, but they are also discarded during the performance, marking a critical moment of resistance and liberation for the performer. The shedding symbolises taking back control over one’s body, identity, and future The final costume embodies the triumph of autonomy and the rejection of the stereotypes and expectations placed on women by societal norms.

The materials for the costumes are more than just decorative; they reflect the narrative of womanhood, identity, and transformation. Revealing the costume layers, from tight and restrictive to fluid and open, symbolises women’s journey to break free from societal expectations, connecting materials to meaning.

Chapter 4: Performance and Movement as the Language of Liberation

In this final chapter, I explore how costume design, performance, and movement connect, particularly how the body can become a powerful symbol of liberation. The body acts as a canvas where costume and movement come together to express the emotional and psychological journey of the performer. Choreography is vital for showing the internal struggles and moments of self-discovery as the costume shifts from being constrictive to freeing.

At first, the movements are slow and restrained, mirroring the performer’s initial entrapment in the societal "Other" role. The body feels stiff, representing the limited expression women often experience under societal expectations. As the costume becomes more fluid, the performer’s movements become more dynamic. The choreography includes expansive gestures that signify liberation, like breaking free from the restrictive costume and reclaiming space. This shift in movement is crucial for illustrating the psychological transition from repression to freedom. The performer’s body, once held back, now flows freely, symbolising the emotional release that comes from shedding societal constraints. Removing the layers of the costume represents rejecting traditional gender roles and embracing a new, self-defined identity.

In the performance final moments, movement is no longer restricted by societal control, and the transformed costume reflects the empowering journey of the performer. This closing sequence of briefly looking back at the past costumes, then walking of screen, shows that womanhood is a complex identity that goes beyond societal limitations and embraces personal authenticity.

Looking back on the rehearsal process, I faced challenges not just with the technical aspects but also in effectively conveying my message to the audience. Experimenting with choreography was crucial for expressing the themes I wanted to highlight. It sometimes took time to find the right balance between movement and emotional depth. Through continuous refinement and feedback, I aimed to enhance the emotional impact of the performance. Incorporating visual elements like images and projections helped amplify the narrative and provide important context. This reflection shows how the techniques used and particular choices contributed to successfully communicating my intentions.

The combination of costume and movement creates an experience that highlights the absurdity of the limitations imposed on women and encourages the audience to consider how these barriers can be overcome. This idea ties back to Enrico Robusti’s exaggerated paintings, which reveal the hypocrisy and constraints of society, particularly in how it treats women.

Conclusion

To conclude, the journey from restriction to liberation is central to this project, to explore the evolving concept of womanhood. Through costume and film, I have symbolised the societal pressures that women face and how these pressures, while pervasive, can be resisted. The work draws on feminist art traditions and performance theory, as well as contemporary movements for gender equality, to create a powerful narrative about the evolving experience of womanhood.

The project explores the cultural and historical pressures placed on women, and it challenges the way people think about gender, identity, and autonomy. My goal aims to encourage the audience to reflect on how gender expectations still shape women's lives and to consider how these expectations can be broken down. Just like Coraline moves between her world and the Other World, women today are constantly navigating the challenges of modern womanhood, finding strength and empowerment while still facing the limits society places on them.

This body of work is dedicated to all women around the world, with a special thought for my family, and in particular my younger sister, whose strength and determination continue to inspire me every day.

Bibliography/References

Adichie, C.N. (2014). We should all be feminists. London: Fourth Estate.

Anon, (n.d.). Fresno Feminist Art Program | The Judy Chicago Art Education Collection. [online] Available at: https://judychicago.arted.psu.edu/about/onsite-archive/teaching-projects/fresno-feminist-art-program/.

BBC (Year) 100 Women. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-41380265 (Accessed: [date you accessed it]).

BPS. (n.d.). Sigmund Freud and penis envy – a failure of courage? [online] Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/sigmund-freud-and-penis-envy-failure-courage#.

Butler, J. (1988). The Changing Face of Womanhood: A Historical Perspective. [Essay].

Chicago, J. (2007) The Dinner Party: From Creation to Preservation. London: Merrell Publishers.

Crispin, J. (2017). Why I Am Not a Feminist. Melville House.

De Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex. Oxford University Press.

Fields, J. (2012). Entering the Picture. Routledge.

Jones, E. (1953). The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud.

Kristof, N.D. and WuDunn, S. (2012) Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide. PBS. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/documentaries/half-the-sky [Accessed 23 Feb. 2025].

Master, W. (n.d.). LibGuides: Reverberating Feminisms: Chronologies of Feminist Art Movements at CalArts: Feminist Art Program (1971–1974). [online] library.calarts.edu. Available at: https://library.calarts.edu/c.php?g=1340092&p=9958608.

Millner, J. and Moore, C. (2018). Feminist Perspectives on Art. Routledge.

MoMA (2010). Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present. [online] The Museum of Modern Art. Available at: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/964.

Munroe, A., Hendricks, J., Altshuler, B., Ross, D.A., Japan Society and Al, E. (2000). Yes Yoko Ono. New York: Japan Society.

Obama, M. (2018) Becoming. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Peace, I. (n.d.). Home. [online] IMAGINE PEACE. Available at: https://www.imaginepeace.com.

Richards, M. (2009). Marina Abramovic. Routledge.

Rippon, G. (2020). THE GENDERED BRAIN : the new neuroscience that shatters the myth of the female brain. S.L.: Vintage.

Royal Academy of Arts (2023). Marina Abramović | Exhibition | Royal Academy of Arts. [online] www.royalacademy.org.uk. Available at: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/marina-abramovic.

Sigmund Freud and Young-Bruehl, E. (2002). Freud on women : a reader. London: Vintage.

Steinem, G. (2019). Outrageous acts and everyday rebellions. New York: Picador, Henry Holt And Company.

Tate (n.d.). Yoko Ono born 1933. [online] Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yoko-ono-1719.

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). 1975 : C’est quoi une femme ? | Archive INA. [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83zaAO6C46Q [Accessed 7 May 2024].